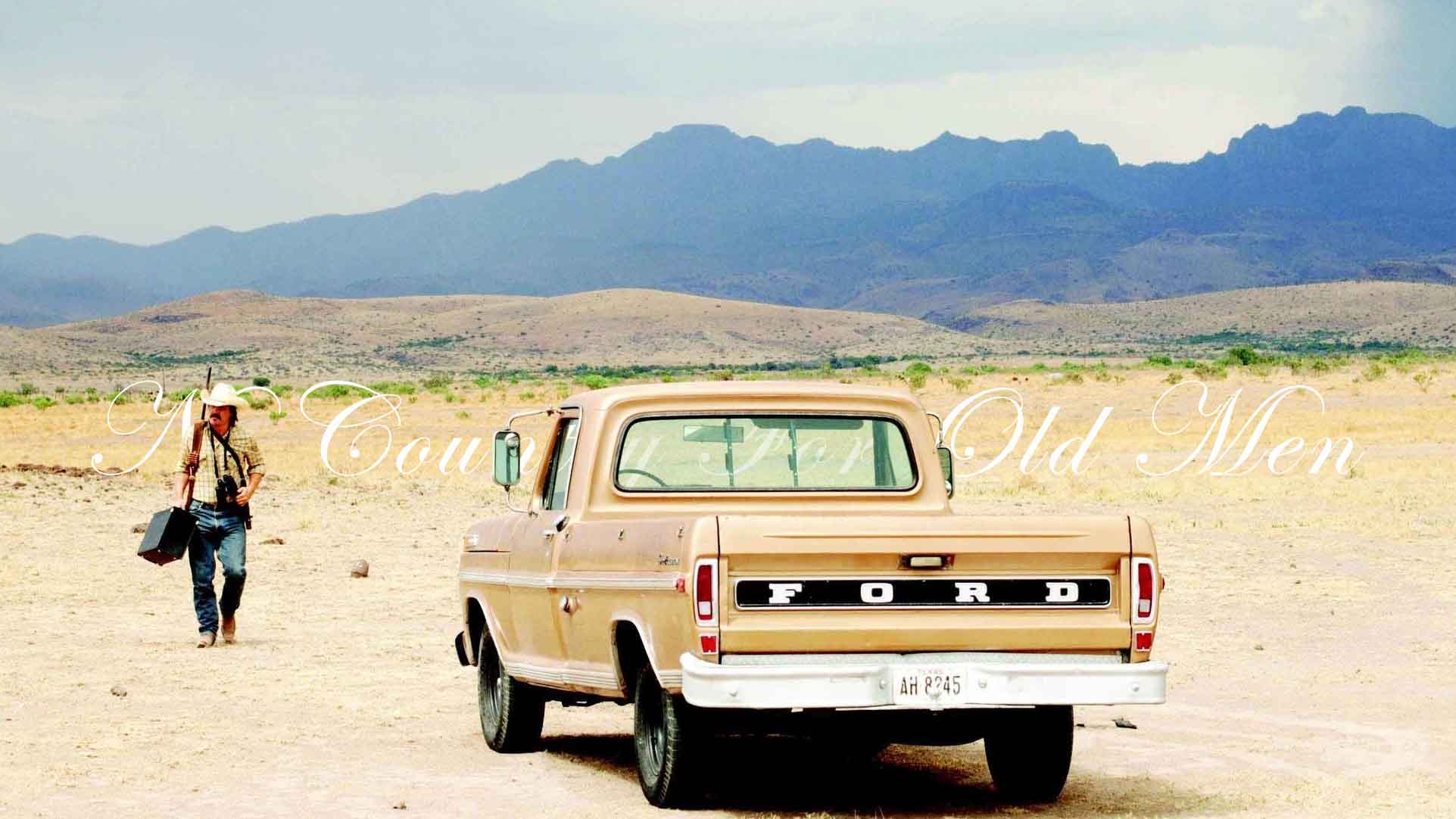

Sukin brought us No Country For Old Men on the movie recommendation widget (you know, the red tab at the bottom of this page?) and I realized I had never seen this historic film from the author Cormac McCarthy. I’d read the book, but never stopped to watch the film. So, thanks Sukin for the movie recommendation, it was pretty amazing, and right up my alley.

Anyway, today’s discussion I’m going straight for the jugular. And if you haven’t had a chance to either read the book or watch the film (the book is decidedly similar to the movie, or vice versa) then you are going to have ruined a true classic.

No Country For Old Men and McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy is a legend. His post apocalyptic novel, The Road, is the book that turned me on to his entire oeuvre. That father and son narrative, replete with zombies and hell on wheels craziness really blew my mind. From there I went on to the Blood Meridian, and from there I was hooked. At this point, I’d read pretty much anything from McCarthy, even the back of a cereal box if given the opportunity. But the thing that is critical to understand about him is that he is the definition of genre busting. He actively works against type, regularly. He takes great pleasure with taking a genre, and the blowing it up from the inside out. So that is the first tip to understanding this movie.

The second, is the importance of dreams and visions in McCarthy’s novels. Here is a great page detailing the importance of dreams in Cormac McCarthy’s book All The Pretty Horses – which I am mainly telling you about because this writer successfully used the word chiastically in a sentence. Ok, ok, I joke, but he shows a pretty good framework for understanding how the author successfully utilizes dreams in the understanding of his writing. But the bottom line is, without an understanding of how Cormac McCarthy utilizes dreams? We are toast with this one friends. But we’ll get to those dreams soon enough.

The Triangle That Is No Country For Old Men

The first character in the important triangle that frames this movie is Llewyn Moss, our everyman. Moss has stumbled upon a horrifying stage set, and discovers the case of cash, and he runs with it. Next in the triumvirate is Anton Chigurh. The psychotic hitman that is attempting to collect the 2 million dollars Moss has taken. And finally we have Sheriff Bell. Bell serves as the story’s moral compass and our narrator announcing the obvious moral decay all around him. And it is among these three characters that our story playing out, and it is among these three that we can discover the meaning of this movie.

So, shall we cut to the chase? If you look at No Country For Old Men from a genre standpoint? It’s awful. Horrible. The Coen brothers?!? What were they thinking? That ending? The emotional crescendo, just to… what? Nothing! It was all for nothing! And the rules of cinema are dogmatic and unforgiving. So what? What is actually happening here? How could one of the best living authors, and two of the best directors of our time, all screw it up so badly?

Well, because this movie is deliberately cutting against the grain of genre, it’s doing it to make a larger point. (Yes! We all know that! But we don’t know what that larger point is, for the love of all that’s good and holy!) Well, maybe a quick overview is in order so that we can count up the final score of the movie and then maybe we’ll be able to tally its meaning.

The “Man” That Is Chigurh

What ever explanation that might be plausible, or half way on target, begins and ends with who, or what, you think Chigurh is. Chigurh, the coin flipping force of nature. Chigurh the sociopathic, homicidal manic, that is so measured, and determined as to make him horrifying. His abilities as a hunter, and his moral code are just so beyond human capabilities.

Think about Moss for a moment. He sees the two million, and he knows that this thing is doable. By marshaling everything within him, he knows that he can outmaneuver whoever it is that might be coming for these two million dollars. And yet, Moss immediately begins losing ground to Chigurh. He doesn’t know it, but we, in our god-like perch do. We see it nearly immediately. So that when Moss goes back out to give the Mexican who was dying in the truck, and in desperate need for water (He can’t have his death on his conscience, now can he? Stealing the money is a different thing. But a death, no thank you.) the account balance was already so stacked against him he almost had no real way of escaping. But to Moss’ credit, he had no idea who it was that was chasing him.

If you insist on thinking of Chigurh as a man – then the ending will thoroughly frustrate, and beguile you. But if you swivel the looking glass perpindicular to yourself, and look at it, and not through it, you might learn more. What specifically Chigurh is will depend on your own personal philosophical vantage. Let’s try a few on for size, and see which one fits the best, shall we?

Chigurh as the Toll of Random Chance

Possibly the simplest interpretation of Chigurh is as a personification of bad luck, or the toll of random chance. It’s pretty simple to see this literally everywhere in the movie. He brandishes his weapons with precision and ruthlessness, and when an individuals time is up, it’s up. The most obvious indication of this is the coin. Several different individuals determine their fate with the toss of a coin. Consider the clueless old timer manning the store. With perpetual joviality, the man attempts to turn the conversation back to the weather, and to pointless topics. And over and over again, Chigurh turns it back to a gambit for the man’s life. If Chigurh is fate, then he is a personification of ill-fated trouble for sure. But is Chigurh just a random meting out of one’s destiny? Really?

Chigurh as the Personification of Death

Chigurh’s path is not random. He is sweeping in a specific direction, and on a very distinct mission. You would think that this random meting out of chaos would have more randomness to it. But what about Chigurh as the grim reaper? Or death? Could it be, that Chigurh is nothing more than the long sweeping scythe of mortality intent on who it might be intent on and winging its way home afterwards? Well, he is an efficient grim reaper, that is for sure. He makes quick work of his victims, and gives them very little afterthought. You can even enlist Bell as the archetypal God-like figure to Chigurh’s personification of death. You can set them up in a duality, yin-yang sort of configuration. A constant struggle between good and evil. Though I would argue, the black on that supposedly equal diagram would be terribly larger than the white. And its that detail that argues against this theory. Bell seems overwhelmed by the very idea of Chigurh, overwhelmed and incapable.

Also, if Chigurh was death, wouldn’t we see some indication of death making his rounds in old folks homes and traffic accidents? Wouldn’t we see a more normal doling out of endings as opposed to murderous death after murderous death? Sure, we could look at the coin toss as death’s constant question, and our occasional escaping. But there seems to be something larger missing in that argument. Some other larger point here that Cormac McCarthy must be making that we haven’t quite alighted on yet.

Chigurh as a Cultural Sweep of Evil & Greed

There is a key scene between Bell and an old friend at a diner. The two bemoan the fact that the world today is beyond them. It is capable of such horrors and atrocities as to be nearly unrecognizable to them both. Here, let me pull the section I’m referring to from the script:

BELL – “My lord, Wendell, it’s just all-out war. I don’t know any other word for it. Who are these folks? I don’t know. Here last week they found this couple out in California they would rent out rooms to old people and then kill em and bury em in the yard and cash their social security checks. They’d torture em first, I don’t know why. Maybe their television set was broke. And this went on until, and here I quote, “Neighbors were alerted when a man ran from the premises wearing only a dog collar.” You can’t make up such a thing as that. I dare you to even try. But that’s what it took, you’ll notice. Get someone’s attention. Diggin graves in the back yard didn’t bring any.”

Yes, Bell is speaking specifically about Chigurh. But he’s actually talking more about life in general. It’s all out war. Yes, the Chigurh thing is all out war. But he’s also referring to atrocities in society in general and the shocking anecdote about the horrors perpetrated on seniors for their social security checks. Evil. More specifically, greed. Society’s new tendencies to do absolutely anything for money.

Think about this thought for a second. Our everyman, Llewyn Moss, he stole money that was not his. The moment he found the cash, the moment he took it with him, his average life went off the rails. Moss wasn’t a psychopathic murderer, but he did begin doing absolutely anything in his power to keep the money. And that particular stain ended his life. It also ended the life of his complicit wife. (Side note, in the book, Carla Jean, was 18 to Moss’ mid-thirties. In the book it was a really obvious difference. A difference that was pointed out clearly.)

Moss was swept up in this societal horror that Bell was bemoaning while reading the newspaper in the diner. Society has pushed off the deep end Bell reckons. Bell sees that the zeitgeist of the day literally is evil and covetousness. Bell isn’t moralizing, or preaching. He’s just wondering what happened. Seniors scrabbling out of homes, wearing nothing but dog collars is about the only thing that shakes us from our slumber. And even that is simply because its titillating.

Pick whichever explanation you prefer. But please don’t think of Chigurh as just a man. Of all the various possibilities, that is the least tenable by a factorial.

The Ending of No Country For Old Men Explained

So the events of the money play out. Time passes a little, Moss probably picks up the money. And then in a confluence of chaos between the mexican drug dealers, Moss, and probably Chigurh, Moss ends up dead. 21 minutes before the movie is over, and our supposed hero is dead. The rest of those 21 minutes deal with three things. 1) The murdering of Carla Jean… 2) The Chigurh car crash. 3) Bell’s two dreams. Let’s take them one by one.

The murdering of Carla Jean. Eventually (we don’t know how much time has passed since the death of Moss) Chigurh shows up for Carla Jean. She says, you don’t have to do this. And he says that everyone says that. Eventually he pulls out a coin and offers her a fifty fifty split. But Carla Jean refuses. She won’t allow her life to be reduced to a game, or some sort of sport. She is calling his bluff and declaring that despite the artifice, Chigurh is the ultimately the one that decides. He is the one that pulls the trigger. Not the coin.

Immediately after that, Chigurh’s impenetrability is lost. He is hit by a car and has a compound arm fracture. He is forced to buy the shirt (using one of the hundred dollar bills from Moss’ stash) and forced to flee the coming police.

And finally, that brings us to Bell’s two dreams. We see that Bell is retired. He’s given up on the search for Chigurh. He’s abandoned the idea of justice and making a difference anymore. Bell has seen the sweeping tide of greed and evil overtake the nation and he wants none of it anymore. He has realized that he is in no position to counter this overwhelming tide.

Bell – “Okay. Two of ’em. Both had my father. It’s peculiar. I’m older now’n he ever was by twenty years. So in a sense he’s the younger man. Anyway, first one I don’t remember so well but it was about meetin’ him in town somewheres and he give me some money and I think I lost it. The second one, it was like we was both back in older times and I was on horseback goin’ through the mountains of a night, goin’ through this pass in the mountains. It was cold and snowin’, hard ridin’. Hard country. He rode past me and kept on goin’. Never said nothin’ goin’ by. He just rode on past and he had his blanket wrapped around him and his head down… and when he rode past I seen he was carryin’ fire in a horn the way people used to do and I could see the horn from the light inside of it. About the color of the moon. And in the dream I knew that he was goin’ on ahead and that he was fixin’ to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold, and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there. Out there up ahead.”

Yeats’ ‘Sailing to Byzantium’

If poetry isn’t your dish – no worries, I got you. The title of the movie, “No Country For Old Men” is a line from a poem entitled Sailing to Byzantium. And whether you like it or not, the first dream is covered in the first couple stanzas of Yeats’ poem. And the second two stanzas covers the second dream. Yeats wrote Byzantium as a declaration of the agony of getting old. Basically he was struggling with remaining vital, dynamic, alive, even when his body was aging and beginning to give out. The solution? To head to Byzantium where the sages could transform him into an “artifice of eternity”. So with that background clarified…

Dream 1 Explained – If you read Yeats’ poem, you will see that it all relates to the vigor and cluelessness of youth. He is given all manner of with in his vitality and his strength, but he wasted it on women, drink, gambling. Basically instant gratification. Bell is stating here that the vigor of his youth drained away, but he can’t remember it anymore. It’s all about the lost years.

Dream 2 Explained – Now, the second dream, Bell gives a lot more detail. Why? Because this particular dream is about Bell right now. The fire represents life, and vitality. Maybe it even represents purity and perfection, or the older ways of living that have been ruined by the current corruption of life. And his father (who died long ago) was lighting the way forward into death and the afterlife. Preparing a place for him after he dies. Bell is realizing that this country is no place for old men.

A Coda on No Country For Old Men

The Coen brothers actually read McCarthy’s book to each other as the other typed as they created the screenplay. So the movie is a very accurate representation of the book. But there were a few key details that I thought might be worth while mentioning. The first being the two kids that talked with Chigurh after his car accident, Bell tracks them both down. The first, David DeMarco – the one that took the money for the shirt, wouldn’t talk… basically the boy kept his promise to Chigurh. The second child actually attempts to help Bell. Which is a fascinating continuance of the metaphor of corruption throughout the story.

And the final detail that I think is worth mentioning is the fact that Bell basically admits that he abandoned his men in Vietnam, and left them to die. The final character in the story that we had any hope of goodness, was toppled by a horrible admission prior to the book’s closing. With this understanding, it is my best guess, that the movie is 100% about the corruptibility of this world, and this life. About our inability to prevent the sport murders of old people for their social security checks. The drug wars that seem to rage all around us. Basically it tells the story of the hopelessness encircles us in every single day of our lives here on planet earth.