There are movies that are meant to entertain. I would say most movies fall into this category. But then, there are other movies that are meant to illuminate. And it is this smaller pile of movies I want to talk about today. Movies that cause epiphanies. Movies that cause one to reassess one’s views of the reality we’ve been sold. That is what American Animals has the potential for doing. Let me put it this way, the American Animals movie documentary about a failed heist, might just be the best philosophy class ever taught.

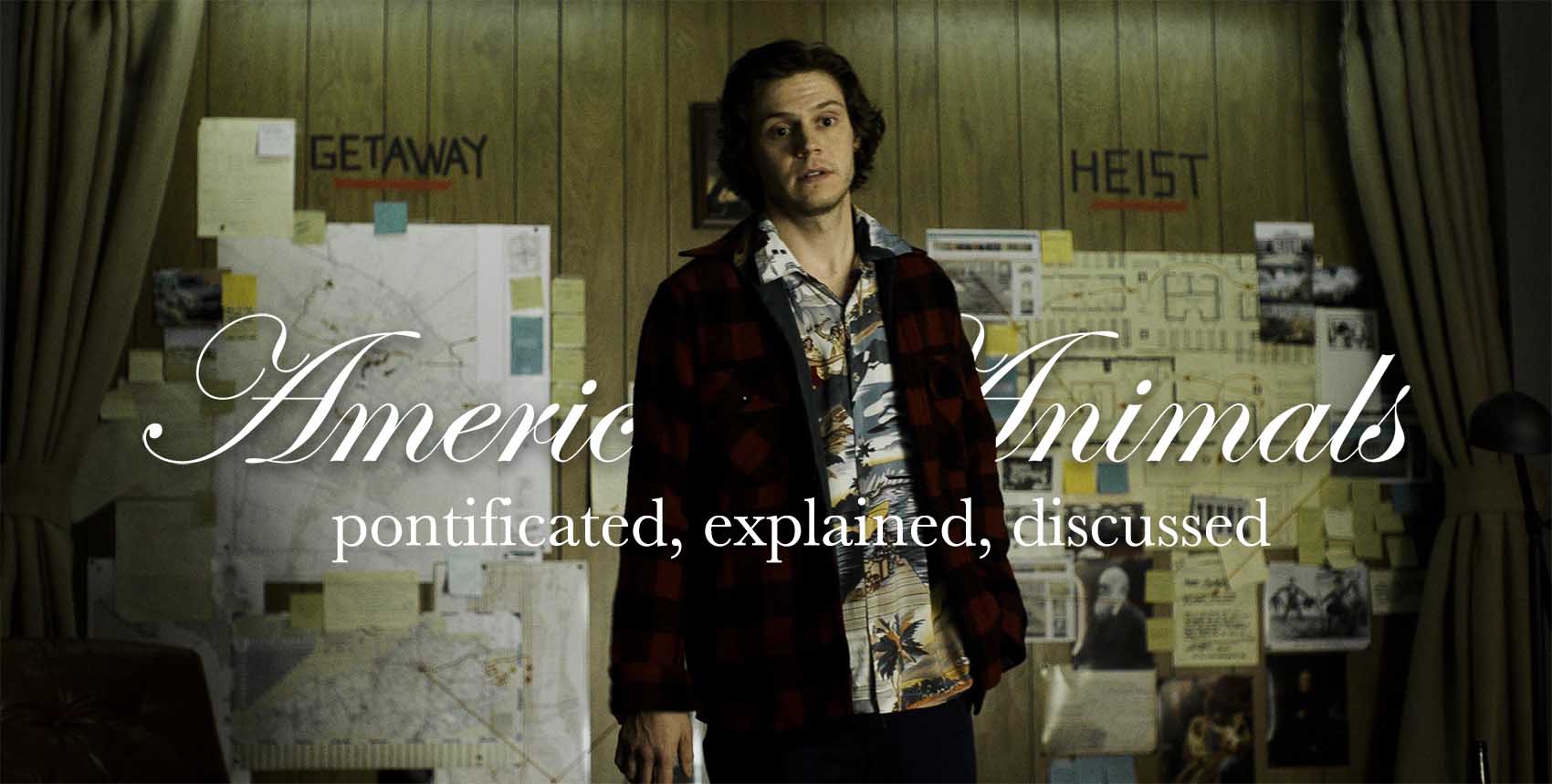

The movie itself is crafted in a hyperreal documentarian fashion. It is cut from the cloth of Borg vs. McEnroe, or I, Tonya – sort of a modern renaissance of documentaries. It’s filmed in a style of reenactment that is self aware and critically self abasing really. We experience a scene acted out, then commented on by the real players of the true events, and then reimagined with a second witness’ perspective added in again. So a scarf goes from green, to purple. A meet up with a fence, goes from with a young Bohemian, to an older gentleman. From black and whites to a variety of grays. It’s a style of cinéma vérité that is so vérité, that it doesn’t even nail down the loose ends in the story.

I am not 100% sure of what exactly is so compelling to me about this method of story telling. Is it the honesty of it? Or maybe the failure of it? Maybe what is so interesting, is to see the actor, or actress, turn down the barrel of the camera and say, “What is it exactly that we are doing here? Doing this thing. Attempting to recount this story? Well, since we are here, why don’t we have a go at it, shall we?”

If you haven’t seen the movie – I definitely give it my highest recommendation. But obviously, it isn’t going to be for everyone. If you are even passably interested in documentaries, I’m betting you’ll enjoy American Animals. If you just like slices of Americana that are just jacked backwards and strange. Then this might just be for you. Heck, let’s be honest with ourselves. You are on this site, a buck says you’ll enjoy it. Just do us all a favor and give it a go. Still unsure? Here, have a trailer.

American Animals Philosophically Digested and Explained

The story is simple enough to understand, you know, all the what’s, the who’s, the where’s. So we’ll go through those at just a high level. But, it’s the why’s that I find most interesting. It is the motivation and the impetus that caused this story even to be real that I find most interesting. And we’ll spend most of our time there, with that discussion – and I may even throw some Kant at you, … because I can.

First things first, I have GOT to start with Barry Keoghan, he of the Dunkirk fame, but more importantly of the The Killing of a Sacred Deer fame. He is an up and comer that we are all going to have to watch closely. Seems like he has a glorious movie selection process. I’m really digging the stuff he’s getting in the middle of. So maybe I craft a Barry Keoghan alert or something that tips us to anything he’s cast in just so we know what we are watching that weekend.

Barry aside, the movie is about Warren Lipka (played by both Warren Lipka and Evan Peters (I just love that parenthetical note just so much)) and his best friend Spencer Reinhard (played both by Spencer Reinhard and Barry Keoghan)). You get the feeling that these two guys have infinite potential, but nowhere to put it. Here, here’s a snippet of conversation they have together that is indicative of the kind of friendship they shared together.

Spencer “So d’you meet any cool people over there?”

Warren “No, bunch of jocks, d’you?”

Spencer “Nuh-uh, it’s not what I thought it would be… ever wondered if you ended up being born you, here, and not someone else? Wherever you feel like you are waiting for something to happen but you don’t know what it is… that thing that could uh, make your life special?”

Warren “Yeah. Like what?”

Spencer “Exactly. Like what.”

There is an aching and a longing that sort of permeates literally every interaction the two share together. They long for important lives that would catapult them into the stratosphere. Well, Spencer, on a tour of the Transylvania University’s library’s rare book collection, realizes these extraordinarily books are only guarded by old librarians and were ripe for the picking. Including James Audubon’s The Birds of America.

And just like that, Warren is certain this is a plan that the two of them are going to have to hatch together. Needing more people to pull off the heist they include Erik Borsuk (played by Jared Abrahamson) and Chas Allen (Blake Jenner). After a failed attempt, dressed as elderly men (which, I have to say was epically brilliant, and extraordinarily cinematic staging for something so real) on their second go, they successfully pull it off… if horrifyingly clumsily.

But the pear shaped heist gets even worse when the guys begin to realize that Warren had been having them on when he said that he had a fence connection from New York that had then coordinated with buyers in Amsterdam. But who knew that you can’t sell art that hasn’t been authenticated? And voila, just like that, they are behind bars.

The Larger Story of American Animals

It seems as if Spencer and Warren were smart, and magnetic personalities about 20 sizes too large for their own good. These college kids had decided that millions of dollars each was going to be the way to take their boring lives and make them something special. But the reality of it is something else entirely. It’s almost as if these guys had watched Ocean’s 11 one too many times. Possibly one of the worst things to steal, ever, is art. Or a one of a kind, first edition book. Why? Because you aren’t selling the art, you are selling the art certification. (Which, I have to add, is how so many fake paintings end up filling art museums, but that is another topic entirely.) So when they commit down this line of logic, while trusting implicitly to Warren’s ‘contacts’, things are definitely bound to go very poorly. One important aspect of this docu-reenactment-drama is that it shows just how unrealistic Hollywood is on this topic of heists.

If I were to heist some extraordinarily valuable piece of art, it’d be because I wanted the painting in my front room. It’s an interesting exercise to consider what painting I’d steal to have with me all the time (which, you’d never be allowed to let anyone enter. Right? Unless you tell everyone it’s a print? And what fun is that?) and if my two criteria were monetary value and just epic gloriousness… hrmmm. I’d probably go with one of Klimt’s portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer. Everyone would probably default to Portrait #1, but I’m not that partial to gold, so I’d go with his second portrait of her. But you’d have to consider the museum it’s housed in, the security of said museum, etc. Maybe I’d have to go with gold instead!? hahah. But, since both are valued at around 100 million dollars, I could go either way.

But what about a heist that you could actually pull off? They are very few and far between. Think about it, whatever it is that you could choose would have to make it worth not ever being able to earn a legitimate dollar again. And if you averaged $50,000 a year for your entire life (if you are reading this blog, that’s a pretty low estimate, even though it’s above the average) that means you might earn 2 million? (Minus taxes and other pesky nonsense.) So, you’d better bring in at LEAST $2,000,000.00 or it’d be a complete waste of your time. And how would we do that? With a standard bank robbery you aren’t getting into the vault. But if you walk out with the money in the drawers? What, 10 grand? No, no. That isn’t even a good used car these days. Insurance fraud? I’ve seen these guys on 60 Minutes that pull something off a grocery store end-cap and pull everything down on top of themselves intentionally in order to take the store for cash. (Come on, this is pocket change!)

Hrmmm. What about hostages and ransom? Man. How do you transfer the money without getting busted at the money drop? Or even if they wire it to an account you are still pretty toast wiring the money out of that account. A man once worked for my father at a school, and he embezzled piles of cash out of their accounts for several years. He eventually was busted and went to jail for a number of years. All for what? $250,000? The risk is decidedly not worth the reward. Oh, and are you willing to dump your moral convictions to walk off with someone else’s cash? Why don’t we talk about that for a moment, shall we?

Kant And His Categorical Imperative

Kant posited that categorical imperatives were the foundations of moral law. They are unconditional or absolute for all people. And the validity of this assumption doesn’t depend on any other end or ulterior motive. The key here is that they are non-conditional. And inversely, he put forward that all immoral actions are irrational because they violate the categorical imperative. Kant believed that a rational will has to be thought of as autonomous in the sense of being the author of the law that binds it. Yeah, it’s getting a little deep in here. But this idea is critical to understanding the Categorical Imperative. At the heart of Kant’s moral philosophy is this idea that reason goes well beyond the idea of human’s being slaves to their passions. Better yet, it is this idea of the self-governing reason that Kant thought offered decisive proof that each of us has intrinsic worth and equal worth… and thus? Deserving equal respect.

But to arrive at that idea of equal respect and equal worth (which, we should all vehemently agree upon) we have to agree to this idea of the Categorical Imperative. Right? These rules that keep us from violating one another’s intrinsic value and worth. Other philosophers like Hobbes, Locke and Aquinas had also argued for moral requirements that were based on standards of rationality, but Hobbes saw them as fulfilling our desires, or external rational principles based on reason, which Locke and Aquinas argued.

So what, yells the post-modernist standing in the bleachers. Well, I would argue, that your lack of belief in a universal Categorical Imperative belittles not only the person you are stealing from, but yourself. But declaring that there is no universal maxim to live by, you are inadvertently saying to everyone around you that your life has no intrinsic value. Wait, what? I said exactly what I meant. You have said that you are valueless. Your own life is bereft of any inherent quality or value by stealing everyone else’s simultaneously. And that is just a non-tenable position to hold long term. Our social fabric only holds together as well as it does because a majority of the people inherently believe in moral absolutism whether they know it or not.

What that means is, if I decide that I want that Klimt portrait for my office… in order to take it, I would need to deconstruct not just rules against stealing… but rules about the inherent purpose of all other humans alive before us and after us. And to side with logic like this? We quickly slip and slide our way to the Third Reich and gas chambers. No? Jews don’t have value. Gas them. Handicapped people are really inconvenient, gas them. Gypsies? No idea, just gas them. And why not? No one has intrinsic value. And all because you want a Klimt portrait all for yourself? I’m not thinking it’s worth it all of a sudden.

The Value of American Animals

And that is where we get to the thing that I adored from the movie American Animals. And it wasn’t that it practically proved how difficult it was to steal a book and fence it. No. It was because it spoke to a larger intrinsic value in others. The movie swung on an axis when it came to the librarian that guarded the books. Spenser and Warren both crumbled when thinking about the harm they put the librarian through. The family members and friends all cracked when thinking about the pain they caused her. Right? And why? Because she was rich? High birth? Exceptionally brilliant? No. It was because she was intrinsically valuable. She was a wonderful woman who did good through her work with books at the university. But heck, if she was a crack head drug dealer, she’d still be intrinsically valuable. Right? And that is the larger moral of this story. These kids were wanting an exceptional life at the risk of everything else, and most specifically putting at risk this librarian’s life. And we all resound with the incivility of this transaction. Right? Personally, I was a little shocked that these guys only got put away for seven years.

Edited by, CY